Antonio Inoki – The Embodiment Of Fighting Spirit

On Saturday October 1st, Japan, and the wider sports world lost a true icon, as the legendary Antonio Inoki passed away at the age of 79 after battling acute cardiac amyloidosis for over a year. His impact across not only the world of professional wrestling, but also on the monumental rise in popularity of mixed martial arts in Japan and internationally cannot be overstated. Inoki’s story is one filled with inspiration, highs and lows, and a number of unfathomable achievements and events, all of which have added to the legend of a man of mythical status amongst pro-wrestling fans.

Born Kanji Inoki on February 20th, 1943, the pro-wrestler-to be was the second youngest of family of seven brothers and four sisters, and whilst the family could be described as affluent at the time of his birth, hard times weren’t far around for the young future megastar. Inoki’s father, Sajiro Inoki, a wealthy businessman and politician, died when Kanji was just 5 years old, a death that further burdened his family as the post-war economy mounted pressure on Japanese citizens. Despite these hardships, Kanji was able to turn his attention towards a multitude of sports that offered an early glimpse into the athlete he would eventually become. In 6th grade he was taught karate by his older brother, and in the following year at Terao Junior High School, he was 180 centimetres tall and joined the basketball team. Inoki later quit his endeavours in basketball and instead joined a track and field club as a shot putter, a decision that would eventually lead him to meet the man that introduced Inoki to the industry he would go on to conquer and change forever. Inoki would go on to win the championship at the Yokohama Junior High School track and field competition, before emigrating to Brazil in 1957 at the age of 14 in order to escape the pressures of post-WW2 Japan, a journey that brought on further hardship as his grandfather passed away during the lengthy journey. Further success awaited Inoki in Brazil despite these troubles, as he won the regional championships in shot put, as well as the discus throw and javelin. Inoki’s track and field career hit its peak when he finally captured the All-Brazilian championships in the shot put and discus, although soon after this he’d step into yet another totally different sport, one that would bring about his greatest successes.

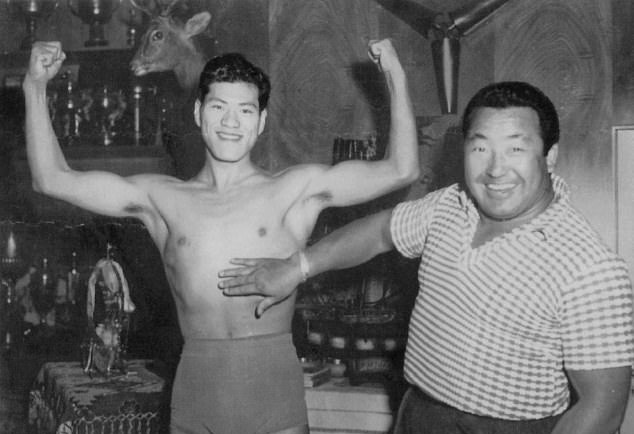

At the age of 17, Inoki met Rikidozan, the man credited by many as being the father of Puroresu in Japan. Having scouted Inoki’s athletic prowess, Rikidozan brought the talented youngster back to Japan with him in order to train him as his disciple for his recently founded JWA promotion. There, alongside his training under amateur wrestler Isao Yoshiwara and kosen judoka Kiyotaka Otsubo, Inoki also trained under the tutelage of the well-renowned Karl Gotch. Gotch would go on to share the ring with his student years later, in a moment that passed the torch from generation to generation. One of Inoki’s classmates during his years training under the JWA was Giant Baba, a man whose career became intertwined with Inoki’s leading the pair down the path of innovation that created the professional wrestling landscape we see today. In the wake of Rikidozan’s murder in 1963, Inoki would find himself stuck in Baba’s shadow, a shadow that Inoki would dedicate his career to battling out of. Seeing that he wasn’t likely to oust Baba from the position of being the JWA’s top star, Inoki headed to the United States on excursion in 1964, where he’d spend two years honing his craft before returning to his homeland in 1966 to start his own promotion alongside ex-JWA president Michiharu Toyonbori , Tokyo Pro Wrestling. Inoki competed for TPW against the likes of Katsuhita Shibata (the father of NJPW’s Katsuyori Shibata) and the future Rusher Kimura, where he shone as the company’s top star. Unfortunately for Inoki, the company folded just a year after its creation due to problems between Toyonbori and his business backers, and thus he made the decision to return to the JWA. Upon his return, Inoki formed a formidable tag-team with the aforementioned Giant Baba under the name “B-I Cannon”, winning the NWA International Tag Team Championships four times during the team’s lifespan.

Inoki could’ve settled for his successes as a tag-team wrestler alongside Baba, although his desire to implement his vision of the sport ultimately lead to his JWA firing in 1971, as he had reportedly planned a hostile takeover of the company. Not allowing this setback to derail his plans to reach the pinnacle of the business, Inoki formed New Japan Pro Wrestling (NJPW) in 1972, a company that many wrestling fans now know as the biggest Puroresu promotion in Japan. Inoki’s first match for the fledgling promotion saw him take on his former trainer and legendary pro-wrestler Karl Gotch, and just three years later the company would also see yet another legendary figure in the sport take in Lou Thesz to the ring with the founder. During his time as performer for the company Inoki held NJPW’s original IWGP Heavyweight Championship twice, first by defeating WWE legend Hulk Hogan on June 14th, 1984, a reign that would last a whopping 701 days, before he gave up the title due to wanting to compete in the 1986 IWGP League. Inoki would go on to win said tournament, thus commencing his second official reign atop of the promotion he founded. This reign lasted just shy of a year, as it was announced that the title would be deactivated in favour of the new IWGP Heavyweight Championship, a title that lasted until March of last year when Kota Ibushi unified the gold with the IWGP Intercontinental Championship. The inaugural champion was to be crowned in the final of the 1987 IWGP League, a tournament that once again saw Inoki emerge victorious, and thus he once again had his own company’s top prize around his waist. This third and final reign with NJPW’s top title once again came just shy of a year in length, as Inoki was forced to vacate the title due to fracturing his ankle. The title would go on to be held by some of the greatest pro-wrestlers of all-time, many of whom were trained and mentored by Inoki. Inoki’s influence over who held the IWGP Heavyweight Championship ultimately began to come at the company’s detriment however, as his emphasis on legitimacy began to hold back some of the talented traditional pro-wrestlers that were breaking through at the time.

In the early 2000s, Inoki began a process of legitimising the wrestling presented by NJPW, ushering in an ideology known by fans as Inokiism. Due to a surge in the popularity of mixed martial arts in Japan, Inoki believed that the professional wrestling stars he had on his roster were no longer seen as true “tough guys”, and thus Inoki decided to come up with a solution: have wrestlers participate in shoot fights and have legitimate combat sports athletes participate in matches. To put it lightly, it was an absolute disaster for the company. Some top stars such as Shinsuke Nakamura and Kazuyuki Fujita found success in MMA, although the majority failed to impress, including the likes of Jushin Thunder Liger, Katsuyori Shibata, and one of NJPW’s biggest stars of the 2000s, Yuji Nagata. One the pro-wrestling front, MMA fighters would often go over some of the fan favourite performers, leading to the likes of Bob Sapp capturing the IWGP Heavyweight Championship much to the dismay of the fans. Between 2003 and 2006, the IWGP Heavyweight Championship changed hands a whopping 15 times, greatly diminishing the titles prestige. Some of the company’s top stars ultimately decided that the promotion was no longer for them, resulting in the likes of Shinya Hashimoto, Keiji Mutoh, Satoshi Kojima, and Riki Choshu leaving for pastures new. The fans also began to voice their displeasure with their wallets, causing attendance and revenue to plummet. A company that once drew impressive crowds of 50-55,000 at the Tokyo Dome were now drawing half of that if they were lucky. The company inevitably found themselves on the verge of bankruptcy, only for Japanese videogame developers Yuke’s to purchase Inoki’s 51.5% ownership of the promotion. This forced Inoki out of the company that he founded and had spent years moulding into his own image for the sport, signifying a new era for what would become the country’s top Puroresu promotion. The majority of MMA stars that had populated the roster under Inoki’s regime departed with their former leader, and the ones that stayed were forced to accept a role more befitting of their talents as a pro-wrestler. In the wake of Inokiism, a young Hiroshi Tanahashi emerged in order to lead the company forward, eventually resulting in the popularity that the promotion now find themselves with.

It wasn’t solely Inoki’s career as a promoter that was shrouded in controversy however, as a number of his in-ring exploits also made a number of headlines during his career. One example of this came in 1976, with Inoki set to take on Pakistan’s Akram Pahalwan in a special rules match. According to the matches referee, Mr.Takahashi, the match’s original flow became undone and developed into a shoot, with Pahalwan at one point biting into Inoki’s arm, leading to a retaliatory eye poke from the Japanese superstar. The bout ended when Inoki locked in a brutal double wrist lock, breaking Pahalwan’s arm after the latter refused to submit. Yet another notorious shoot involving Inoki happened just a year later, as he took on former strongman turned pro-wrestler The Great Antonio, in a match that saw the heavyweight inexplicably no-selling Inoki’s offence, until Inoki eventually snapped, taking the big man to the ground, and delivering a pair of devastating kicks to the face, before stomping his head into the mat until the match was called off. As The Great Antonio eventually returned to his feet, fans were met with the sight of a busted open and bloody Antonio, a stern reminder that Inoki was more than capable of handling business if you weren’t willing to play ball with him.

One of Inoki’s most famous championship victories came on November 30th, 1979, as he defeated the then-WWF Heavyweight Champion Bob Backlund in Tokushima, Japan, to claim the gold. Backlund got his win back on December 6th of that same year, although WWF President Hisashi Shinma declared the bout a no-contest due to interference from Tiger Jeet Singh, and thus Inoki remained champion. Inoki, however, refused the title that same day, and thus the WWF Heavyweight Championship was vacated. Backlund would go on to defeat Bobby Duncan in a Texas death match on December 12th, to regain the title, with WWE’s official championship lineage not recognizing Inoki’s reign, and thus Backlund’s reign between 1978 to 1983 remained untarnished. As a result, there has yet to ever be a WWE Champion hailing from Japan, although many have clamoured throughout the years for the company to finally recognise Inoki’s reign as legitimate, particularly following his recent passing. Whilst Inoki may have never officially captured WWE’s top prize, he did receive his well-earned Hall of Fame induction in 2010, cementing his place amongst legends of the industry both in America and internationally.

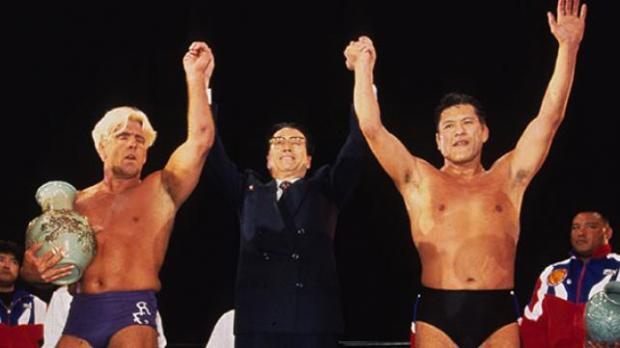

Perhaps Inoki’s most infamous wrestling performance came on April 29th, 1995, as he was a part of an event in Pyongyang, North Korea, organised by the governments of Japan and North Korea in order to further establish peace between the two nations. NJPW and American promotion WCW came together to present the best talents they had to offer in a two-day event that reportedly drew a mammoth crowd of around 165,000 and 190,000 fans respectively to the Rungnado May Day Stadium. The main event of Day 2 saw the only bout between Antonio Inoki and legendary American wrestler Ric Flair to ever take place. Prior to said main event, the Pyongyang crowd sat silently, either bemused at what they were seeing or simply disinterested in the sport that they’d been made to watch for two days. Then the main event happened. Inoki, having been announced prior to the match as being the protégé of the Korea-born Rikidozan, was deemed the hero of the match against the villainous Flair, utilising the foreign heel trope that American wrestling has often utilised on their own programming. As discussed by Flair on multiple instances, the crowd responded to nothing during the entire event, no matter the calibre of wrestler put in front of them, that was until Inoki emerged, and the fans in attendance finally rallied behind a star they felt they could identify with. Inoki won the bout by pinfall following an enzuigiri, bringing an end to quite possibly the most bizarre pro-wrestling event ever held, and one that saw a wave of difficulties faced by the talents involved.

This for Inoki, was a chance for him to further his burgeoning political career, one that began in 1989 as he attempted to follow in his late father’s footsteps. Inoki was elected into the House of Councillors in 1989 as a representative of his own Sports and Peace Party, and it wouldn’t take long before Inoki began making headlines in the political world. Imitating Muhammad Ali’s foray into politics, Inoki travelled to Iraq in “an unofficial one-man diplomatic mission” and successfully negotiated with Saddam Hussein for the release of Japanese hostages before the start of the Gulf War. In order to do this, Inoki presented a wrestling event in Iraq with the aim of freeing 41 Japanese nationals, a goal that was largely met as he returned having freed 36 nationals. Whilst in Iraq, Inoki converted to Shia Islam, and was bestowed the Islamic moniker Muhammad Hussein, however later in his life he claimed that he practiced both as a Muslim and a Buddhist, although he prioritised the latter. Inoki subsequently retained his seat in the 1992 Japanese House of Councillors Election as a result of his successes, although he failed to retain his seat in the 1995 Elections following a number of scandals that had been reported on a year prior, sparking Inoki’s departure from politics for the next eighteen years, until his return as an MP in 2013. This second stint lasted until 2019 and featured a number of further attempts to establish peace between his home nation and North Korea, attempts that even featured a number of controversial trips to the communist nation.

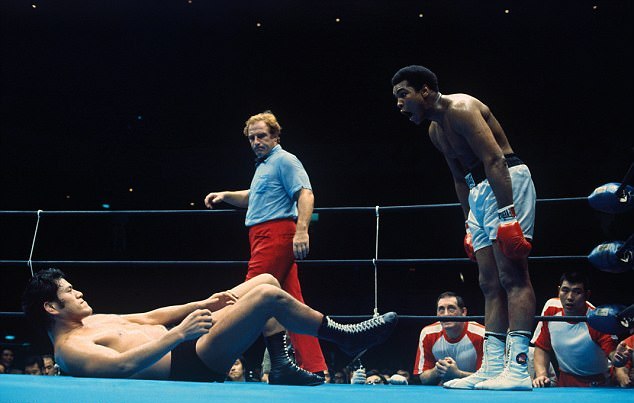

Having honed his craft under the tutelage of Karl Gotch, Inoki was influenced heavily by professional wrestling’s catch wrestling roots, and thus he developed his own method of fighting, which he dubbed “strong style”. This particular style of the art of pro-wrestling is still to this day associated with New Japan Pro Wrestling, with Inoki’s influence having left an impact on shoot wrestling like no-one before or after him. The development of said style would go on to influence the creation of organisations such as Shooto, Pancrase, and RINGS, all of which played a monumental role in the rise of mixed martial arts in Japan and the wider world, and thus Inoki’s innovation can be seen as the first domino that fell on the path towards the popularity of MMA seen today across the globe. One of Inoki’s most memorable moments could be seen as a direct ancestor to what we now know as mixed martial, as the larger-than-life personality stepped into the ring with perhaps the greatest boxer of all time, Muhammad Ali, on June 26th, 1976, in front of a sold-out crowd of over 14,000 at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo. The bout was originally proposed to Ali as a rigged contest in order to persuade the global superstar to accept the offer, although upon the deal’s materialisation, Ali feared that Inoki would attempt to turn the fight into a shoot, and thus a number of rules were laid out that ultimately led to a very legitimate, albeit a convoluted and underwhelming, crossover of styles that pitted two of the best in their respective fields against each other. During the match itself, Inoki utilised a rule that had been implemented only two days prior to the contest to his advantage, as it was stated that he could throw kicks at the heavyweight boxing legend as long as one of his knees was on the ground. As a result, rather than try and engage Ali and show off his impressive catch wrestling skills, Inoki instead spent the majority of the fight on his back, as he repeatedly swiped at Ali’s legs. The match ended in a 3-3 draw, following a display that frustrated the Tokyo crowd beyond belief, as neither man was able to effectively display their skills due to Inoki’s antics. Despite the bout failing to live up to its lofty expectations, there can be no doubt Muhammad Ali vs Antonio Inoki is the highest profile MMA contest of all time, with the concept laying the groundwork for the success of organisations such as the UFC that was to come years down the line.

All of the incredible events that transpired in Inoki’s remarkable life resulted in the Japanese superstar achieving a legendary status in his home country. Perhaps the greatest representation of the mythical status that Inoki achieved is the creation of what became known as the “Fighting Spirit Slap”. The story of said slap is said to have originated during a visit Inoki made to a school in the 80s, as Inoki was punched twice by a student at the school. Inoki retaliated by slapping the youngster, knocking him down. Rather than complain that a visitor of the school had struck him, the young pupil, who turned out to be a fan of the pro-wrestling superstar, instead rose to his feet, bowed deeply, and thanked Inoki for the slap he had just received. The incident became a national phenomenon and appeared across Japanese television a number of times. As a result, numerous celebrities, Japanese citizens, and even the entirety of Inoki’s locker rooms at times have requested that Inoki slap them to instil his fighting spirit into them as almost a strange sort of blessing. One particular instance of this occurred at Inoki’s Bom-Ba-Ye show in 2000, as Inoki delivered a whopping total of 108 slaps to a queue of backstage workers and talents that seemed almost never-ending at times.

The wrestling world has lost perhaps the most enigmatic figure in the history of the industry, the likes of which we’ll never see again. His accomplishments are endless, his controversies are unfathomable, but his fighting spirit and desire to leave his mark on the world are what Antonio Inoki will always stand above the rest for.

Genki ga areba, nademo dekiru. – If you have spirit, you can achieve anything.